|

Green Politics in Canada In February 1983, a new era began in Canadian politics. Approximately 200 British Columbia environmentalists and peace activists formed an organization under the rubric of the "Green Party" and announced that they intended to contest several seats in the upcoming provincial election. Not to be outdone by their B.C. counterparts, a group of environmentalists in Toronto announced the formation of Green Party of Ontario (GPO) three months later. During this first year, the Greens "sprouted" chapters throughout Canada and attracted more than 4,000 members. However, while chapters of the Green Party spread quickly, the infrastructure necessary to support a political organization had been firmly laid only in Ontario and British Columbia by the time of the party's first national convention, held in Ottawa in November 1983. The conference, titled "The Gathering of the Greens," was supposed to launch the party on a national level and consolidate the early progress the organizers felt had already been made.

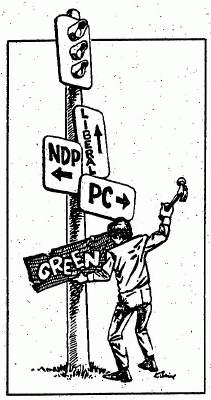

These early initiatives motivated the formation of provincial Green parties in Quebec, Manitoba, Nova Scotia, and Alberta over the ensuing two years. They also inspired individuals in other regions of the country to form chapters which may one day provide a framework for a truly national party. Considerable excitement and enthusiasm characterized these first stages of Green politics in Canada. The burst of energy that certain organizers injected in the Canadian Green parties gave the impression to some people that Green politics had indeed arrived in this country. But it was almost as if success had been too easily achieved. Critics suspected this was the case and predicted an early demise for the Greens. They pointed out that many of the policies advocated by Canadian Greens were part of the platforms of the New Democratic Party (NDP), on both the provincial and federal levels. Bob Rae, leader of the NDP in Ontario, told a reporter for Maclean's magazine in December 1983 that Green politics was irrelevant in the Canadian context. Since Rae's remark much of the interest and optimism that the Greens initially generated in the media and among those concerned with the transformation of our political institutions has died down, and the jury is still out on the future of the Green parties. This indeterminacy would seem to result from the nature of Green politics. The fundamental values that Greens promote, such as local control and consensus decision-making, appear to be in conflict with attempts to broaden their political support base. Moreover, nothing short of a cultural revolution will satisfy many Greens. They argue that the real problem facing the industrialized world is a crisis of values, a lack of spiritual development' and the growth of centralized, hierarchical institutions which rob people of their role in decision-making Intervention in these aspects of private life transcends conventional notions of democratic politics. However, recognition of the need to intervene at these levels in order to promote alternative technology and devise new "behavioral solutions" to environmental problems seems to have grown in recent years.

It is important, therefore, to consider just what it is that the Greens in Canada and other parts of the world are advocating. Ecological politics may contain the seeds of a process, which, when combined with the goal of building a Conserver Society, will reorient our society in a fundamental way. The unanswered question is whether the difficulties facing advocates of Green politics can be overcome in this country. The main difficulty is related to the way policies are developed by the Greens. Individual chapters retain a large amount of control over policy making Policies are shaped at regular meetings which usually attract a reasonable percentage of the chapter members. For example, the Toronto Chapter of the GPO has approximately 350 members and an active core of participants that brings out more than 30 people to meetings. However, many of the smaller chapters have fewer than 50 members and usually only a handful of individuals keep these chapters going. This emphasis on local control has encouraged a divergence of views on how best to intervene politically to protect the environment. Historically, most Canadian environmentalists have preferred to employ an approach loosely termed "environmental politics." This approach includes techniques such as political demonstrations and protests, education, nonpartisan lobbying, and working within the established parties, for example, to promote environmental law reform. Through the practice of environmental policies, environmentalists claim to have realized some of their aspirations for environmental protection or conservation. In contrast, those attracted to the Greens in Canada so far are more strongly oriented to partisan politics. However, serious questions can be raised about the future success of this approach. Recent federal and Ontario provincial election results show that the Canadian public is not ready to vote for candidates running for the Greens. The failure of Canadian Green parties to attract electoral support and the difficulties encountered in the formation of an official party machinery appear to have vindicated early critics, Questions have also been raised recently about the continued vitality of Green politics in Canada. For example, former members of the GPO who have left the party in the past few months are disenchanted with the present state of the party in Ontario. Some of these former members doubt whether the Ontario Greens can continue to be called a viable political entity. There are two major reasons why there is limited support for the Greens: Green parties in Canada are seen to be imported, and the Greens are generally seen as being a one-issue party. Green parties in this country are perceived by many Canadians to be an imported response to environmental and social problems. These people have gained awareness of the Greens through the success of the West German party (Die Grunen). That group has achieved considerable political support for their environmental and antinuclear platforms. The West German Greens, which formed a party in 1980, has consistently earned around five per cent of the popular vote over the past four years. This share of the vote has "translated" into approximately 27 seats in the Bundestang (the West German Parliament) as well as seats in the state and local councils. The West German Greens' electoral success reflects the system reflects the system of proportional representation in that country which provides seats to parties that voice the concerns of minority viewpoints. In contrast, most parliamentary democracies in the English tradition stress a form of representational politics in which "the winner takes all." While the 27 seats held by the West German Greens are not a large number in terms of the overall numbers of delegates to the Bundestag (496), the Green presence has brought about numerous environmental reforms which the traditional parties would have either avoided or delayed implementing. The charge that Green parties are an imported, partisan approach to environmental issues probably does have some validity. But the notion of ecological politics should not be viewed as a new philosophy about politics. Canadians have been aware of the notion, which was born of the counterculture movement in the 1960s, for almost two decades. However, it was not until the early 1970s that people in the industrialized nations concerned about the deteriorating state of the environment actually began to suspect that fundamental changes were required in our political system. Ecological politics was the alternative proposed. In theory, this new form of politics would bring environmental issues into the forefront of decision-making. While the practice of environmental politics accepts most of the precepts of modern democratic society, ecological politics takes a different approach. For example, ecological politics rejects hierarchy and competition as a basis for social and economic relationships. Green parties are one type of response to the desire of supporters of ecological politics to make other people aware of this alternative view of the political process. Another approach would emphasize nurturing a "Green Movement" - a network among various groups interested in alternative technology, holistic health care, antinuclear protest, and environmental protection. Ideally, these two levels of change would take place simultaneously. These different perspectives within the worldwide Greens have generated a fundamental rift between those who want to gain power in almost any way and the anarchistic. anti- party Greens who emphasize sensitizing people to environmental issues and changing attitudes and values. The former group sees as most urgent the need to bring pressure to bear on politicians in order to protect the environment and stop the arms race. The anarchists, who are willing to work within chapter structures, argue that gaining this kind of power compromises the revolutionary goals of the Greens. This split over what approach to take to fundamental political change has haunted the Greens over the past decade and continues to be a source of controversy in Canada. The Greens who advocate the former approach trace their inspiration to the publication of the January 1972 issue of the British magazine, The Ecologist. That issue, titled "Blueprint for Survival" proposed that a national political party in Britain was required to deal with environmental problems in a substantive way. Not long after the publication was distributed, a group of environmentalists in New Zealand formed the Values Party. The following year a similar group emerged in Britain, calling itself the Ecology Party. For a brief time period, both these parties attracted a considerable measure of support, although they never elected any representatives. Since that time, however, the Values Party has collapsed in New Zealand, and the Ecology Party has failed to gain political power in Britain. There, as in Canada, representation is non-proportional, and potential supporters see a vote for a minority viewpoint as a waste. The apparent legacy of these early developments in Britain and New Zealand is the existence of Green-Style parties in most of Western Europe, Australia, Japan, Mexico and the United States. In addition, Greens hold seats in the European parliament and in several countries where proportional representation is practiced. The other main reason why the Greens have failed to receive political support in Canada is that they are generally perceived as a one-issue party. For example, some critics claim that the Greens separate their concern for the environment from other important social and economic issues. In response to this charge, Trevor Hancock, a Toronto physician and founding member of the Ontario Greens comments: "Sure we are a one-issue party. The issue is the survival of the planet. If you're looking at the transformation of social values, that has implications in all dimensions of public policy." Hancock's point highlights one of the major dilemmas that the Greens face in attempting to publicize their aspirations. The media often has a tendency to reduce complex political policies to slogans. The significance of the holistic nature of ecological politics is simplified in the process. Consequently many people who dismiss the Greens as a fringe party are unaware of what advocates of this approach to politics are really saying. Perhaps the most progressive aspect of Green politics is the rejection of the traditional political spectrum as a basis for interpretation of existing economic, social and ecological problems. West German Greens, for example, have attempted to incorporate individuals from all shades of the political spectrum into their party organization. As Fritjof Capra and Charlene Spretnak observe in their recent book, Green Politics: The Global Promise ,the slogan of the West German Greens - "We are neither the left nor right, we are in front" - encapsulates the essence of this view. The old ideological battle lines, they argue, are no longer relevant to the problems of a society on the brink of ecological catastrophe. According to Capra and Spretnak, the West German Greens embrace four basic principles - ecology, social responsibility, grassroots democrat and nonviolence. Implicit in these founding principles is another important concept; decentralization. This implies a de-emphasis of nation-state ideology and a reaffirmation of the significance of regions in both an ecological and social sense. Other principals which are tied to this concept of decentralization include a rejection of hierarchical and patriarchal institutions, and an emphasis on self-development and individual spirituality. Nevertheless, it should be pointed out that the West German Greens have agreed officially on only the four basic principles noted above, and the adoption of these latter beliefs has generated considerable controversy. In addition to the four core principles, various Green parties from all over the world have put forward policies in the social and economic sphere. For example, according to the manifesto of the British Ecology Party prepared for the 1983 election in that country, the goal of the Green economics would shift from growth to sustainability. Such a shift would require significant improvement in recycling, soil conservation, renewable energy use, and other "soft paths" in the technical realm. Moreover a sustainable economy would necessitate considerable institutional renovation. Expanding on this theme, the British Greens argue that urban-industrial society is ruled by "dinosaur" corporations and institutions which control the allocation of capital, energy and resources. These large corporations promote inefficient use of resources and often seem unable to respond to fluctuations in the demand to their products and service without extreme difficulty. The Greens reject increasing centralization in the corporate sector and advocate a type of qualitative shift in our socioeconomic structure that would encourage greater work flexibility and smaller-scale cooperative businesses. This approach to economics also has considerable implications for social relationships. Consequently some Greens argue that greater work flexibility, job sharing and cooperative business ventures would require new approaches to leisure, child care and other activities. An important feature of Green politics is the open nature of the decision-making process. Murray Bookchin, an environmental activist and author of numerous books on the social ecology of modern urban industrialism, noted at a Toronto International Youth Conference in August of this year that the West German Greens are attempting to radicalize democracy and re-inject a sense of empowerment into decision-making. Bookchin maintains that "people are not citizens. They have been reduced to constituencies who merely vote and taxpayers who merely pay. They play no role in the political process that exists today. Hence we need new politics." Bookchin's recent involvement with Greens in Vermont has convinced him that empowerment can be achieved through "thinking globally and acting locally." This is a catch phrase employed by the Greens to describe their sensitivity to the need for local action rather than the mere articulation of platitudes. Examples of such statements, well-intentioned or not, include those made daily by politicians about the need to stop polluting the biosphere or to save starving people in Africa. While Bookchin admits these are important problems, he contends that, rather than attempting to look elsewhere for problems to solve, we should start with our own problems at home. This means one should try to heal relationships in local communities and the family as a first step toward an ecological politics. In order to radicalize democracy, Greens seek maximum participation in their political processes and emphasize the principle of consensus. This latter principle makes decision-making a rather tortured process. Invariably it is difficult to achieve more than 70 or 80 per cent agreement on the implementation of a policy or the selection of a Green for a position in the party machinery. The pluralism of values and experiences that members bring to the Greens seems to preclude attainment of a higher degree of agreement. Nevertheless, it should be noted that majoritarian politics (i.e., requiring a 51% majority) often ignores dissenting voices who have an important contribution to make to decision-making. Counterbalancing this is the fact that representational politics allows for more rapid responses to opportunities in competitive situations. The "reality" poses a major challenge to the idealism to applying the model of consensus decision-making in the industrialized West. Another distinction between Greens and traditional political parties is the rejection of personality-oriented politics. Accordingly, the West German Greens "rotate" their parliamentary representatives every two years in order to prevent the centralization of power and knowledge that characterize adversarial politics in the West. Unfortunately, this practice has run into difficulty at the national level in West Germany, primarily because of tensions between the desire to publicize the success of the Greens and the fear of personality politics. Spokesmen like Rudolf Bahro (author of the book Socialism and Survival) and Petra Kelly have garnered international recognition for their speaking tours. This has flared debate among the decentralist "antiparty" Greens on how to balance the tension between publicizing Green activities and minimizing personality politics. The West German Greens are experiencing a "crisis of conscience" as a result of this type of tension. However, the more significant the dilemma they now face relates to the fact that in some areas of West Germany the Greens have gained the balance of power in provincial and municipal governments. Consequently they are being forced to choose between compromising their revolutionary goals and gaining a significantly greater role in decision-making through the formation of coalitions with more traditional parties, such as the Christian Democrats and the Social Democrats. Presently it is unclear how these conflicts will be resolved or whether they, in fact, are even resolvable. While evaluation of the success of Green politics in Europe thus far reveals mixed results, assessing the impact of the Canadian Greens is more difficult. In Europe it is clear that the presence of the Greens has widened the content of the current political debate. However, in Canada the impact of the Greens to date has been relatively small. While the Greens did encourage discussion of specific environmental issues in the recent Ontario provincial election (such as pollution in Toronto's Junction Triangle area), they have been ineffective in their attempts to initiate a critical discussion of social transformation along the lines proposed in their theories of decentralization and the promotion of economic sustainability. Moreover, their nonpartisan activities, such as organizing nonviolent protests to the logging of Meares Island in BC, have often attracted far more media attention and public interest. The participation of the BC Green Party in the 1983 provincial election also generated some cynicism about the Greens in general. After the election writ was issued in Victoria in February 1983, a few individuals took the "bull by the horns" and propelled the fledgling Green Party into frantic canvassing for new members and aggressive campaigning for electoral support. However, time was unavailable prior to this intense electioneering activity to identify and debate the philosophy, policies and goals of the party. Consequently, the BC Green Party campaign platform degenerated into motherhood statements about the need to implement policies favouring environmental protection and an end to the arms race. As Frank Tester, who teaches at the Faculty of Environmental Studies at York University observes, "it is apparent to many people that these statements were being made in order to exploit concerns over the arms race and the pollution of Canadian lakes from acid rain, thereby gaining political power, rather than to bring about social change." Despite the last-minute efforts and lack of clear policies, the BC Greens attracted as much as four per cent of the votes cast in certain ridings, support which appears to have been gained at the expense of the BC New Democrats. However, the impact of the BC Greens does not seem to be related so much as they deprived the BC NDP votes. Rather the Greens challenged the NDP to adopt more radical policies and this might have influenced voters to move right and re elect the Socreds. In view of the recent history of the Socreds in making cutbacks to social programs and environmental research, one could understand why interested people would be cynical about the Canadian Greens. The long term implications of the BC campaign for the development of Green politics in this country are still not known. However, many observers and political supporters quickly labeled the Canadian version of the Green Party as a colourless imitation of the audacious and inspiring West German Greens. It is an image that Canadian Greens have been unable to shake. This fact is supported by the reaction of the Canadian electorate to Green candidates in the recent federal and Ontario elections. In the 1984 federal election, more than 50 Greens contested seats. Eighteen of the candidates were from BC, and 27 were from Ontario, but Greens also vied for seats in Alberta (7), Quebec (4), Saskatchewan (2), and Prince Edward Island (1). The aim of participation, according to the Greens who wanted to run candidates in the election, was to make the public aware that their version of ecological politics had indeed arrived.

In terms of actual impact where politics in democratic decision-making matters - the public's response to the arrival of Green politics in Canada was disappointing. The party gained some support, but in no case did the Green vote surpass the gap between the runner-up and the winner of any of the ridings. Moreover, while the Greens came in ahead of the other "minor" party candidates in Ontario, the BC Rhinoceros Party and the Western Canadian Concept Party in Alberta frequently attracted more votes than Green candidates. Electoral support for the Greens seems to be greatest in the Southern Ontario ridings in and around Toronto. The Toronto chapter of the Green Party of Ontario (GPO) fielded 11 candidates in the 1984 federal election. These candidates received 600 votes per contested seat, which translated into less than two per cent of the popular vote. Whether or not this result should be viewed as a success is open to debate, but the Greens certainly did add a new dimension to the Canadian electoral process through participation in the 1984 Tory sweep to power. The federal election ultimately proved a major drain on the financial resources of the different chapters that ran candidates. Some chapters subsequently collapsed, and many individuals seemed to burn out during the fundraising activity that followed. This may explain why the Toronto Chapter decided to run only five candidates in last spring's provincial election. Although only 11 Green Party candidates ran into the election in Ontario, and the GPO attracted a total of 6,053 "votes for change." The most popular candidate for the Ontario Greens was Chris Kowalchuk, who received six per cent of the vote in the riding of Oakville. However, the other Greens received just under two per cent of the vote (on average) in the seats they contested, duplicating the federal results from last year. Most of the initial organizers of the GPO remain undaunted by their lack of success in elections. Hancock observes that "gaining support through the electoral process will be a long and difficult struggle, but it is one that has enormous value in terms of public education. Another reason the Greens have had difficulty getting established in Ontario and other parts of Canada is that the New Democratic Party has reassured its supporters that Green policies on environmental protection and disarmament are mainly slogans. According to Brian Charlton, MPP for the Hamilton Mountain and current NDP energy critic at Queens Park, this hasn't been very difficult. He says that "The reason why the New Democrats in Ontario would relegate the Ontario Green Party policies to slogans is that "the Greens haven't dealt with a whole range of other issues, such as unemployment, which are of major concern in Ontario politics." Support for this interpretation of the performance of the Greens in Canada has been expressed in the media as well. As Kevin Arnett notes in an article on the Greens in the November 1983 issue of Canadian Dimension, the "anti-socialistic rhetoric" of the Greens sounds "surprisingly akin to the bombast of early Social Credit preachers Bill Aberhardt and Major Douglas." He goes on to comment that the real challenge now for the Canadian left is to revitalize its ideas through a genuine exchange with the Greens. In this way the left can minimize the drift of disillusioned voters to the right or to alternate parties such as the Greens and the Libertarians. Presently these disillusioned voters appear to have provided most of the support for Canada's Green Party. Many Greens are former NDPers pr ex-Liberals who became jaded with the apparent inability of those parties to come to grips with the radical implications of a Conserver Society. It is the holistic and forward-thinking approach of the Greens that attracts these "defectors." Whereas the established parties remain mixed in their rhetoric of compromise with labour unions and big business, the Greens argue that the fundamental assumption embraced in the 19th century logic of liberal democratic politics - that economic growth can continue unabated with reforms to existing policies - is flawed. Greens believe that this assumption of continued economic growth and increasing material prosperity has dangerous implications in the long run, and that the only way to escape this flawed logic is to move away from our consumer-oriented culture into a Conserver Society. Translation of these broad principles into policy has proven a complex task. In Ontario, the Greens have divided into study groups which examine problems such as war and disarmament, environmental issues, women's issues, economics, health, and so on. Nevertheless, the wide range of ideological views that must be reconciled sometimes results in polarizations. While Greens claim that their values bind them together, it is often apparent that they have very different interpretations of the social policies that extend from the principles they advocate. For example, attitudes among Ontario Greens on economic policy range from support for small-scale capitalism to radical socialist perspectives. Unfortunately this kind of discrepancy posed all sorts of communication problems at meetings and policy forums. Consequently, it has prevented some chapters from developing coherent policies. It should not be surprising that environmentalists view the arrival of the Greens on the Canadian political scene as a mixed blessing. While many individuals support the Greens' goals and principals, they are skeptical of the value of getting caught up in the politics of social transformation advocated by the Greens. There are too many pressing tasks, such as pollution of the Great Lakes, to be addressed within existing political frameworks to justify the kind of investment that the Greens are making in academic and time-consuming discussions about democratic processes and consensus decision-making.

Perhaps the key failing of the Ontario party so far is the stress that has been placed on electioneering. Green activists in Europe are involved in developing grassroots networks of groups (i.e. the Green Movement described above) which link up cooperative housing initiatives and other self-help projects. In Canada it appears that the Greens do not yet operate in this "multilevel" sense. Thus, where the West German Greens are the "political arm of the citizen's movement" according to Capra and Spretnak, Canadian Greens have yet to link together environmental groups, Cruise Missile protesters, and alternative projects in health care, women's rights, the social control over technology, and so on. This difficulty also highlights the debate over whether the objectives of the Greens are better served through informal networking as a movement, rather than attempting to organize as a party. In nations without proportional representation, such as Canada, it probably makes more sense to promote the philosophy of the movement without actually participating in electoral politics. As Hancock observes, this would provide the Greens with some political clout and might force the NDP and other parties to adopt more radical policies on certain environmental issues. Similarly, questions have been asked about whether the Greens should actively attempt to split the left-wing vote in Canada. To this point, with the exception of the 1983 provincial election in BC, Greens have not garnered sufficient votes in any one riding to have altered the distribution of power. However, it is not that farfetched to imagine such a scenario emerging in the future. Presumably, though, the Greens could wield similar kinds of political clout as a movement. Determining exactly what the balance between electioneering and networking should be in Canada promises to be a controversial issue for the Greens. It is apparent that the party cannot continue to participate in federal and provincial elections without more money and public support. Nevertheless, recognition of the inevitable failure of participation in elections in these forums may open opportunities for Greens in municipal elections. Shirley Farlinger, the current spokesperson for the Toronto Chapter and a candidate for the Greens in the riding of Rosedale n the 1984 federal election, supports this approach. "I think the Greens should run in municipal elections," she says, "because we are a grassroots organization. We believe in decentralized decision-making." As Farlinger also points out, the opportunities for Green participation in local politics are substantially greater than those available to Canadian Greens in the other two forums. Whether or not the Greens decide to favour running candidates in municipal elections remains an open question. However, it is apparent that if Canadian Greens fail to refocus their activities, they could disintegrate. The departure of members from the GPO poses a stern warning to all Canadian Greens to adopt a more pragmatic attitude. Otherwise they risk fulfilling Bob Rae's prognosis of irrelevancy. David McRobert is a Fellow in the Faculty of Environmental Studies at York University and a student at Osgoode Hall Law School. He was a founding member of the York University/Downsview Chapter of the Green Party of Ontario. Autumn 1985 Probe Post |